|

Back to Suisun Valley History Archives Town Histories

From Goerke-Shrode, Sabine (2005), Images of America: Fairfield, Arcadia Publishing, San Francisco, CA, 127 p.

For nearly 150 years, Fairfield has served Solano County ... as the seat of its county government. Yet despite its political prominence, Fairfield was an artificially created city and was overshadowed by its neighbor and rival, Suisun City, for the first 75 years of its existence. Well into the 20th century, Fairfield did not have many residents. Most people lived in the surrounding valleys, using Fairfield for their bureaucratic needs. Suisun, with its port, was the commercial hub that everybody turned to for trade, commerce, and entertainment. Despite the fact that Fairfield served as the seat of county government, it didn't even have its own post office in the early years. Fairfield Timeline (Modified from: Fairfield City Official Home Page, 2019) Prehistory:The earliest native inhabitants of the Fairfield area were the Suisun Indians who settled in the Rockville and Green Valley areas. Artifacts uncovered by excavation teams in Green Valley include those of the Ion culture, dating back five to six thousand years. These discoveries are some of the oldest traces of Indian settlements in Northern California. 1810:Gabriel Moraga, the first known white man in the area, is sent by the Spanish to lead an army in an attack against the local Suisun Indians. Although resisting fiercely, the Indians are finally forced to retreat. Many of them reportedly set their own huts on fire after realizing the battle was lost and perished in the flames. 1835:General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, under order by the Mexican government, arrives to colonize the Suisun area and create a buffer zone against the Russians at Fort Ross. A major battle ensues between Vallejo's forces and several Indian tribes led by Chief Sem-Yeto where the Soscol Creek and Napa River meet. Eventually, Vallejo's forces overpower the Indian tribes. Vallejo is not a tyrant in victory, however, and he and Sem-Yeto become allies, joining forces later on against hostile tribes. 1837:Chief Solano applies to the Mexican governor for a land grant for his people. The grant, titled Suisun Rancho, is approved and covers most of Suisun Valley. However, the Indians do not fare well in coexistence, and approximately 70,000 Indians die in the next three years from a smallpox epidemic brought in by the Russians at Fort Ross. In 1842 Chief Solano sells his grant to General Vallejo for $1,000 (the same grant was sold eight years later to A.A. Ritchie and Captain Waterman for $50,000). In 1850 Chief Solano and the remaining Suisun tribe move to the Napa area, which is not yet extensively colonized. 1856:Captain Robert H. Waterman lays out the townsite of Fairfield, which he names after his hometown in Connecticut. A clipper ship captain who had sailed around the world five times, Waterman decides to settle in Suisun Valley with his wife, Cordelia (for whom the Cordelia area of Fairfield is named). In 1858 Waterman makes an offer to the county government to have the county seat moved from Benicia to Fairfield. The proposal is placed on the ballot and ratified by the voters in the November election. Thus, Fairfield becomes the new county seat. As promised, Waterman donates sixteen acres of land to the county, at the corner of Texas and Union Streets, for new county buildings. In 1860 the first county buildings are constructed (a brick courthouse and jail were built for $15,400). 1903: Fairfield is formally incorporated as a city. 1942:Travis Air Force Base is built by the U.S. Government on a tract of land located to the east of Fairfield, and gives a tremendous boost to the local economy. This base becomes one of the major departure points for military units heading for combat in Vietnam. The base was annexed to Fairfield on March 30, 1966. Today:The city's location, natural amenities, and abundant land sites are some of the attributes that make Fairfield a great place to live. The population of Fairfield has increased from 3,100 people in 1950 to 106,502 in 2009. The city and surrounding areas remain one of the most desirable urban growth centers in the Bay Area, even in trying economic times.

From DeCaro, Elissa and Ewing, L.M. (2013), Images of America: Suisun City and Valley, Arcadia Publishing, San Francisco, CA, 127 p.

Valleys awash with golden wild oats; hills carpeted with dewy grass under the shade of ancient, plentiful oaks; the glimmering surface of the marsh teaming with life—these are the timeless vistas of the wondrous Suisun region. ... It is awe-inspiring to consider the immense biodiversity of the area. There were birds and fish by the thousands, grizzlies and tule elk roaming free, and an unending supply of acorns, soap root, and native plants. It is no wonder the Suisunes Indians [who lived here] thrived for thousands of years prior to Spanish occupation, sustained by the seemingly limitless supply of natural resources. It is also no wonder Suisun City would become the central trade link between San Francisco and Sacramento. Suisun City Timeline (Modified from: Official Suisun City Home Page, 2019) Prehistory:Set on the banks of the California Delta in Solano County, Suisun City takes its name from the adjacent Suisun Bay, which in turn is named for the Suisunes, a tribelet of Southern Patwin Indians whose village (rancheria) was located in the area. 1849:Suisun City was established in the 1850s around the time of the California Gold Rush. During that time Suisun City's was the ideal location for commerce and transportation between the foothills and the bay area. The town was a beehive of activity; wagons, carts, buggies, cattle, horses and men filled the streets. In the 1850s, the principle business in Suisun City was the sale of grain. It was the shipping point for the very productive Vaca, Suisun and Green valleys. Schooners were constantly in Suisun Slough headed for San Francisco and Sacramento with their cargo. The buildings in Suisun City indicated its mercantile prosperity. Located in the center of town was a flourmill that was constantly operating. There were also blacksmith shops, tin shops, saddleries, carpenter shops and many other industries in operation. Suisun City was known in some circles as the mercantile center of Solano County. 1869:The Transcontinental Railroad connects to Suisun City, expanding the region’s reach across the nation. It was the first train stop in Solano County, California, and continues as the county’s only passenger rail stop to this day. 1906:A major milestone in the history of the entire Bay Area was the great San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Suisun City suffered little damage but didn’t escape the “jolt.” 1916: Suisun's Mayfield Hotel.Though Suisun City escaped physical harm, its good fortune didn't last. A fire swept through town a few months later, destroying about half the residential section, the train depot, the creamery, several packing sheds and other buildings. This fire changed the face of Suisun City forever. Today:The spirit of commerce is enjoying a renaissance in Suisun City. Popular restaurants dot the waterfront promenade area. Cyclists pose in front of Suisun's Arlington Hotel in the early 1900s. New business activity is brisk with several new dining establishments, an art gallery, and a 102-room hotel now open for business. The city is quickly becoming a popular destination for a day trip or even an overnight getaway. Activities abound for nature lovers and water sports enthusiasts. Kayaking, fishing, bike riding, bird watching, hiking, Suisun Wildlife Center programs, and popular events are just some of the reasons that visitors are drawn to Suisun City from throughout the Bay Area and beyond.

From Bowen, Jerry (2004), Images of America: Vacaville, Arcadia Publishing, San Francisco, CA, 127 p.

In 1842 Manuel Vaca and Juan Felipe Pena came from New Mexico to California and settled near Putah Creek, then called the Lihuaytos River or Lihuaytos Creek. They applied jointly for and were granted a ten-league (one league equals about 4,500 acres) Mexican land grant called Lihuaytos. In actuality, due to the vague description of the boundaries, it actually covered in excess of 20 leagues overlapping the Rio de los Putos grant belonging to William Wolfskill. On August 21, 1850, Juan Manuel Vaca sold a square English league of land, which is actually nine square miles, for $3,000 to William McDaniel with the provision that one square mile be designated as a new town of Vacaville. In addition, McDaniel was to deed back to Vaca 1,055 lots in the new town. Vaca, who spoke no English, thought he was only selling one square mile of land. McDaniel had made an arrangement with lawyer Lansing B. Mizner that he would deed over half of the land in the deal with Vaca to Mizner in exchange for laying out the city and tending to the legal paper work. Mizner was fluent in both Spanish and English and acted as interpreter for the transaction with Vaca. While translating, it isn't clear if Mizner made it understandable to Vaca how much actual property was involved. The deed was written only in English instead of both languages. During translation, it isn't known if the term "one English league" (about nine square miles) was used or if the actual boundaries laid out in the deed were made clear. At any rate, the deal was made and Vaca placed his "X" on it. In 1851 Mizner laid out the new town of Vacaville, and McDaniel deeded the required lots to Vaca. When Vaca discovered McDaniel was preparing to sell large portions of the other eight square miles at a tidy profit he informed McDaniel that the way he had understood the deal was that he had only sold one square mile, which was to become the town of Vacaville. Vaca placed an ad in the California Gazette in May 1851 stating, "Caution. I hereby notify all persons not to purchase any lands from William McDaniel, which he claims to have purchased from me under title that he obtained under false pretenses and I shall institute suit against him to annul the title so fraudulently obtained by him. [Signed] Manual Baca [Vaca]." McDaniel had been in negotiation with a couple of buyers with cash in hand. After reading Vaca's notice in the newspaper, the buyers informed McDaniel that they did not want to buy a lawsuit along with the land and backed out of the deal. McDaniel filed a libel lawsuit against Vaca and the case went to trial on October 30, 1851, before Judge Robert Hopkins. Vaca hired the firm Jones, Tomkins & Stroube to represent him, the same firm that had bungled his land grant case before the land commission on his first application to ratify the grant according to the Treaty of Hidalgo provisions. Vaca lost the case and the jury handed down a judgment on October 31, 1851, awarding McDaniel the sum of $16,750. Vaca filed an appeal to the state supreme court. After reviewing the evidence, the supreme court set aside the judgment against Vaca on February 5, 1852. In their opinion there was no malice in the notice. In addition, the lower court's proceedings were rife with sustained objections and overrulings that had no place in law, as well as other monumental mistakes in the proceedings. It is not certain if Vaca ever filed suit against McDaniel for the alleged fraudulent deal. Vacaville was laid out and a map filed with the county on December 13, 1851. Vacaville started to grow as settlers began arriving. It is interesting to note that not even the original map was followed with its Spanish-named streets. The original trail into Vacaville had much to do with this as did the future property owners for whom the streets were eventually named. Vacaville Timeline (Modified from: Official Vacaville Home Page, 2019) Prehistory:The earliest native inhabitants of the Vacaville area were Southern Patwin Indians, whose village (rancheria) of Malacca was located in the Lagoon Valley area on the south side of modern Vacaville. Another Southern Patwin rancheria was the village of Ulatato, which was located along Ulatis Creek in the main part of Vacaville. 1841:Juan Manuel Vaca and Juan Felipe Peña arrive in California and the following year obtain a Mexican land grant. The Peña Adobe is erected in Lagoon Valley the same year, and Vaca and Peña in 1845 receive full title to their land grant from the Mexican Government. 1850:William McDaniel, a former U.S> Congressman from Missouri, purchases land from Vaca, and agrees to create a township from one square mile of the land. The deed is recorded Dec. 13, 1851, and the township named "Vacaville." 1892:Vacaville incorporates as a city. 1921:Historic Nut Tree restaurant and gift shop opens on old U.S. Route 40. In its heyday the Nut Tree contained a full restaurant, bakery, multiple shops, and the Nut Tree Railroad that transported visitors to the Nut Tree Airport. In 1996 the Nut Tree closes after a 75-year run due to financial problems brought on by increased competition and changing consumer tastes. Today:An outlet center on the opposite side of the I80 freeway from the old Nut Tree restaurant opens up in 1988, and when the Nut Tree itself reopens in 2009 as an outdoor shopping center, Vacaville transforms into one of the premium shopping districts in Northern California.

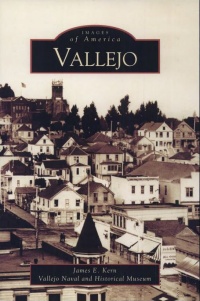

From Kern, James E. (2004), Images of America: Vallejo, Arcadia Publishing, San Francisco, CA, 127 p.

Vallejo has always been a "crossroads community," a city of transitions. The earliest inhabitants of the region traveled through the area where the city of Vallejo is now located, but for the most part they did not stay. The Suscol Native American tribe to the north, the Suisun tribe to the east, and the Karkins, who lived along the straits that later would bear their name, all came to this area to gather tules to build their homes, hunt in the grass-covered hills, and fish in the abundance of the bay. But usually they returned to larger nearby villages and did not settle here permanently. Europeans first came in the 1770s, but they too were just passing through. Members of an expedition led by Lieutenant Pedro Fages first saw the straits, the lush green hillsides, and the long, low island at the mouth of the Napa River in March 1772. Three years later, Jose Canizares, a member of the de Anza Expedition, drew the first map of the area and called the island Isla Plana—the flat island. But these were explorers, not settlers, and they continued on their way. In 1833 a young California named Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo passed through the area on his way to Sonoma, where he would take up the post of commandante of Mexico's northern frontier. General Vallejo obtained several large Mexican land grants and one of them, the Rancho Suscol, included the land where the cities of Vallejo and Benicia would later be built. Vallejo raised cattle for hides and tallow, and maintained a small garrison of troops at the Sonoma Barracks. Transportation was usually on foot, by horse, or by boat. A popular story holds that Vallejo was transporting horses on a boat across the Carquinez Straits one day when the vessel capsized and the horses were swept into the water. Vallejo's favorite horse, a white mare, swam ashore on the Isla Plana and, after she was rescued, the island gained a new name: Isla de la Yegua, or Island of the Mare. As Vallejo advanced his career and increased his power in northern California, he became more and more convinced that Californians would best be served if they annexed themselves to the United States. Mexico was losing its tenuous grip on the northern frontier, and General Vallejo realized that the westward-expanding American empire would eventually reach California, and that Californians had better be ready for its arrival. But events moved more rapidly than even Vallejo could anticipate. The Bear Flag Revolt in 1846 and the discovery of gold in 1848 changed California dramatically, although the ever-reliant General Vallejo stayed ahead of the game. When California was admitted to the Union in 1850, Vallejo offered 156 acres of his land to the State of California to build a new state capital. General Vallejo proposed that the city be named Eureka, but a grateful state legislature named the new city Vallejo in his honor. In 1852 the state capital moved from San Jose to Vallejo. Now the seat of state government, the town of Vallejo welcomed the state legislature with open arms, but the government officials also would just be passing through. Primitive conditions in the newly-built city forced the legislature to move, first to Benicia and then to Sacramento. Another transition. In 1854 the U.S. Navy arrived. The navy acquired Mare Island and there they established the first U.S. Naval Base on the Pacific Coast. As Mare Island grew, the city of Vallejo grew along with it. But as a maritime port, Vallejo would continue in its role as a "crossroads community." Sailors and their ships came and went. The civilian workforce at Mare Island grew and declined and grew again, reflecting the many vacillations in America's military and political life. Along with its identity as a navy town, Vallejo also became a center of trade and transportation. The railroad arrived in the 1860s and connected Vallejo with other communities in northern California and, ultimately, with the rest of the United States. Ships of all kind came and went, from scow-schooners transporting goods across the bay, to ferries carrying people between cities, to naval and commercial vessels from the four corners of the world. Within this maritime city, businesses connected to sea-going trade thrived. Lumber was shipped through the Carquinez Straits to build the cities of the growing state of California. Grain was shipped from the fruitful Central Valley where it was milled into flour at Vallejo and then continued on its journey to the cities of Europe, Asia, and South America. These many businesses and industries also provided the opportunities for a better life that attracted new residents from across the United States and all around the world. Immigrants from China, Japan, and the Philippines reflected Vallejo's connection with the Pacific Rim. Other immigrants arrived from South and Central America and from European nations like England, Ireland, Germany, Portugal, Italy, Russia, and France. The city became a crossroads for the world. From its rough-and-tumble pioneer beginnings in the 19th century, Vallejo grew in the 20th century into a diverse and thriving community, supported by the reliable federal payroll at Mare Island. New highways, bridges, civic buildings, and comfortable homes reflected the stability of this solid, mostly blue-collar community. The United States broke out of its isolation and became a player on the world stage. Mare Island grew to support that role, and so too did the City of Vallejo. As America became involved in foreign affairs, Mare Island supplied the ships that supported that involvement. The Spanish-American War and World War I brought growth to the city and the shipyard, but their impact would pale in comparison to the tremendous changes caused by World War II. That tumultuous era brought unprecedented growth to Vallejo and saw the city's population nearly triple. Once again, people from all over the United States came to the "crossroads community" to work at the busy shipyard. Thousands of sailors passed through Mare Island to the Pacific War Zone. Many never returned. When the war ended, many civilian workers went back to their home states. Others remained in Vallejo and built homes in the new post-war neighborhoods that sprang up east and north of the old part of town. The next transition would come in the early 1960s when city fathers decided to demolish much of old downtown Vallejo and build a new, forward-looking town center and civic plaza. Surrounding rural land was annexed and the city continued to grow. Vallejo faced the challenges and social changes of the 1960s and emerged with its strong sense of community intact. Vallejoans are, and always have been, avid sports fans, supporters of the arts, believers in education, strong in their faith, and have demonstrated the true essence of community spirit. And although they have come to this "crossroads community" from all around the world, and for a variety of different reasons, Vallejoans love their city and continue to work together to make it thrive.

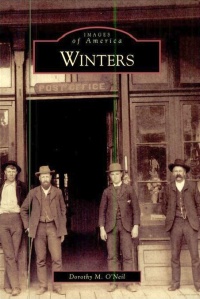

From O'Neil, Dorothy (2009), Images of America: Winters, Arcadia Publishing, San Francisco, CA, 127 p.

A land of rich soil and gentle climate lying along the western edge of the Sacramento Valley, the Winters area was once home to the Patwin Indians, a friendly people who welcomed the Spanish explorers. California became a Mexican Republic in 1821, but one of the last acts of the Spanish governor was to send an expedition to explore the Sacramento Valley. This led the Mexican Congress to open up grants to settlers in order to cultivate the land. William Wolfskill, a Mexican citizen who helped establish the Santa Fe Trail, would receive one of the first of these grants. The Wolfskill brothers came from Fort Boonesborough, Kentucky, to Missouri and grew up with the Boone, Cooper, and Carson families. It was William's brother, John Reid Wolfskill, who settled on the grant he named Rancho Rio de los Putos and was credited with being the father of the fruit industry in Winters. Continuing the friendliness of his Native American predecessors, he gave many new settlers starter seeds and root stock and was famous for his "jerky line" left for the hungry traveler. After gold was discovered at Sutter's Mill in 1848, a mad rush began to California. Over mountains and desert, braving Native American attack, hunger, and cholera, the forty-niners began pouring into the state. Some of these forty-niners, discouraged with the gold fields or enriched by them, began to come to the area to settle. By the time California became a state in 1850, word about the rich land here had spread, bringing more pioneer families. John Wolfskill was joined by brothers Milton, Mathus, and Sarchal. Mathus began a ranch south of Winters Bridge, which he sold to Theodore Winters in 1865. By 1857, a town had begun to develop at a crossroad in Buckeye, a township of Southwestern Yolo County. Soon afterwards, sales of tracts from the rancho brought in more settlers, who worked together to clear the land, hunt the feared grizzly bears, and open wagon roads to markets in Sacramento and Suisun Bay. In 1875, a rail line was extended across Putah Creek near the Wolfskill ford, and a depot and town were mapped out with assistance from D.P. Edwards, Theodore Winters, and others who needed transportation for their crops, horses, and livestock. The town of Winters, established partly by Buckeye residents who picked up their buildings and moved them on logs into the new town, grew quickly and, by 1876, had become a busy agriculture and commercial center with three trains daily, several new businesses, hotels, saloons, a Wells Fargo Office, and many new homes. The first major crops were barley and wheat, but soon fruit orchards were producing peaches, almonds, plums, pears, cherries, figs, and oranges. By 1890, thousands of acres of fruit and nut trees were producing abundantly. So many families came from Missouri that the early Winters newspaper, the Winters Advocate, included Missouri news. By the turn of the 20th century, new waves of Japanese and Spanish families began to settle in the foothills surrounding Winters, where the soil, deep and fertile, produced firm and early-ripening fruit prized in the world market. Apricots became such a big part of the local economy that Winters became known as "Apricot City." Today the train depot and the railroad tracks are gone. The dam built at Devil's Gate was completed in 1957. The new reservoir, named Lake Berryessa in 1956 by President Dwight Eisenhower, has replaced upper Putah Creek Canyon and the neighboring town of Monticello. Winters is no longer called Apricot City; it is now called the Gateway to Lake Berryessa. Yet agriculture is still the mainstay of the local economy, and the spirit of friendliness and the strong values handed down from pioneer families are still evident.

INDEX to towns in the above summaries

|